Boeing Robotic Wingbox

2012

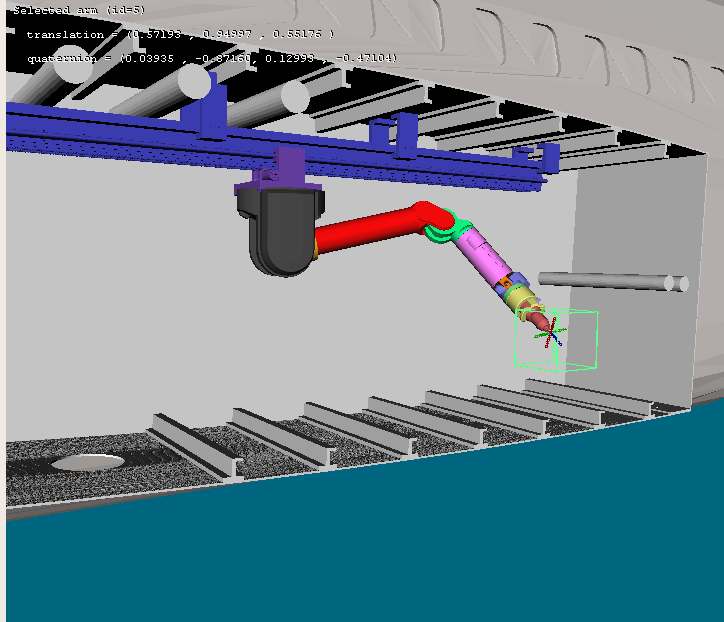

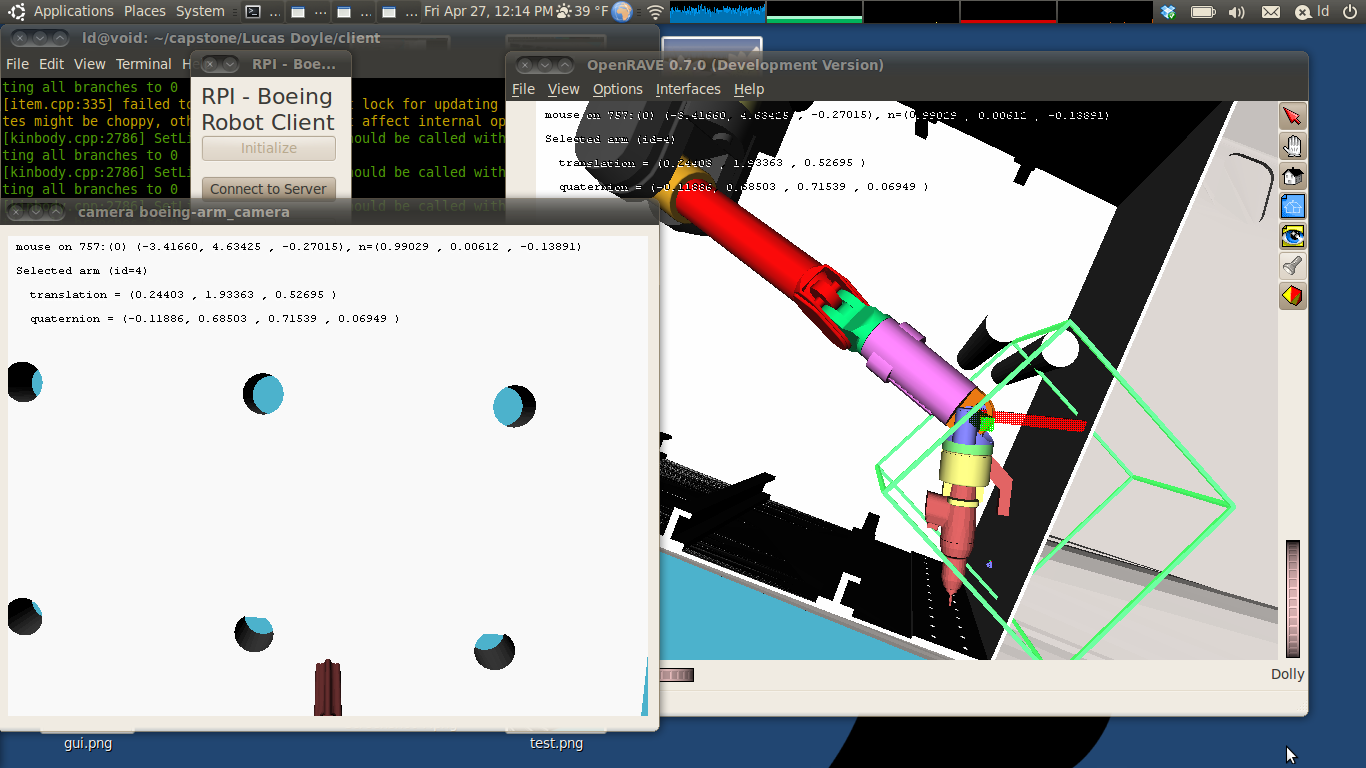

A robot that performs maintenance from inside an aircraft wing. Developed as part of my Boeing sponsored capstone project. Our team was specify tasked to develop a simulation and control system for this.

I served as the project lead, where I was responsible for coordinating with Boeing as well as writing all of the code for the simulator (other members of the team were not familiar with programming). I also did a lot of report writing.

Architecture

The general architecture of the system was split into three parts: a client, server and simulation data.

Operation started with the client to coordinate and control the robot. Using joysticks, a 3d rendering of the robot in its environment and a video feed, the operator could modify the client's simulation environment to be in some new desired state.

The operator could then send this modified state to the server, which would do all the heavy computations necessary to smoothly and safely transition the robot from current state to the desired state. The server also did other computationally intensive tasks, such as object recognition of things like bolt holes. Ultimately, the server was designed to control a physical robot, so an abstraction layer was developed to allow generic information from the simulation to be translated into hardware commands. Support was also implemented between client and server to allow many clients to safely control a single robot server via conflict resolution.

Finally, all the simulation data (descriptions of the kinematic bodies that comprise a robot, the location and contents of the simulation environment, etc) was kept separate to increase flexibility and portability of the software as it was used in both the client and the server.

Why

So why do any of this? The wings of a modern commercial aircraft are one of the most complex and precisely manufactured objects mankind has produced. They not only provide the lift and structural support that allow the aircraft to fly, but also house many critical pieces of equipment such as fuel lines, hydraulic pumps, electrical wires, hoses, etc.

This equipment is kept spaces inside the wing called wingboxes. Unfortunately these wingboxes need to be human accessible, which introduce a significant ergonomic constraint into the overall wing design.

To date, Boeing has access holes cut in the outside skin of the wing, which compromise the structural integrity and decreases the aerodynamic efficiency of the wings while adding weight.

Boeing is very interested in developing a robotic system that could operate inside the wing to assist with assembly and maintenance tasks. This would remove the ergonomic constraint, increase the structural and aerodynamic efficiency of the aircraft while decreasing weight. The cost savings from decreased fuel usage alone would be huge. This solution would also carry with it the benefits inherent to robotics: increased speed, repeatability and accuracy during assembly and maintenance.

What I learned

This was a big project for me, and I am immensely proud of how the final product turned out and had a ton of fun working with RPI and Boeing on the project.

The biggest lesson I learned was how to manage time. If I could do anything different I either wish that I wasn't team leader so I could spend more time coding, or someone else on the team also could have also coded along side me so I could be a better leader. I felt spread too thin between coding this massive application and also being a manager. I would rather do one thing and do it well as opposed to do two or more things and not be able to give each my best.

Shout outs

My capstone team:

- Sairina Mirchandani

- Amber Mosal

- Chris Low

- Edward Shambeau

- Sam Michon

From the RPI Design Lab for their excellent guidance, especially when it comes to the management side of things:

- Casey Goodwin

- Joshua Hurst

- Mark Steiner

From Boeing for their technical input and valuable feedback:

- Jamel Bland

- Hillary Barr

- Mark Goldhammer

Rosen Diankov for his assistance and OpenRAVE, a really helpful library